- Major US Infrastructure networks overhaul planned if legislation passes

- Infrastructure equities provide proven benefits to investors

- Private finance and privatisation likely to be required

- Will experienced, foreign operators be able to access the build-out?

The US government’s ambitious plan to overhaul the country’s infrastructure networks over the next decade provide a huge opportunity for investors, but uncertainties abound: how much of the proposed legislative framework will eventually be voted through, how to buy into what assets. and how much access foreign operators will be able to secure.

The landmark Legislative Outline for Rebuilding Infrastructure in America was released in March. By providing $200 billion of federal funding over a 10-year period, the government aims to raise a total of $1.5 trillion to develop new and upgrade existing infrastructure.

The plan outlines $100 billion in incentives to support investment in surface transport, airports, passenger rail, ports and waterways, flood control, water supply, hydropower, water resources, drinking water facilities, wastewater facilities, storm water facilities, and Brownfield and Superfund sites. In addition, $50 billion is earmarked for a rural development programme focused on roads, bridges, public transit, rail, airports, maritime facilities, broadband, water, waste, electrical transmission and distribution networks.

Funding and political influences

Another $20 billion Transformative Projects Program will fundamentally change the way infrastructure is delivered or operated and will include ground-breaking projects with significantly more investment risk than standard infrastructure, but a much larger reward profile.

Another $20 billion is set to expand existing Federal credit programs and broaden the use of Private Activity Bonds (PABs). Further, the Legislative Outline suggests relaxing restrictions on tolling interstate highways, streamlining rules governing passenger facility charges at smaller airports, and starting to commercialise interstate highway rest areas. Restrictions on airport development, including privatisation, would be eased.

However, the chances that the entire plan will be converted into legislation before the US November mid-term elections are remote. Increasing the role of the private sector in developing and running infrastructure assets is likely to face opposition from Democrats, and Republicans may not approve another $200 billion of federal spending in the wake of US tax law changes, further expanding the overall budget deficit.

Infrastructure equities

If the legislation is eventually passed, the infrastructure categories prioritised in the Legislative Outline will become major targets of government funding, providing an interesting tailwind opportunity for investors. Yet infrastructure operators per se may not be the main beneficiaries.

The main attraction of infrastructure operators is that they are underpinned by significant physical assets and generate cash flows from their fixed asset base that extend far into the future. Consequently, they are less likely to be impacted by current events than the wider market. Many infrastructure companies provide services that are vital to the effective functioning of societies, so demand for their assets is highly inelastic. Often, their revenue base is governed by inflation-linked tariffs, so returns should meet and/or beat inflation over the long-term. Certain subsectors such as social infrastructure earn their revenues exclusively from the lower-risk public sector.

In a recent analysis by Credit Suisse analysing which stocks will benefit from the infrastructure plan, virtually all the equities mentioned belong to the capital goods, materials, project management, technology and real estate sectors. These types of companies have little in common with true infrastructure operators. Contractors and building materials suppliers operate in an exceptionally cyclical environment, with high variability in revenues, backlogs, margins and cost overruns. Those operating internationally can be significantly impacted by currency fluctuations. Their valuations reflect their volatility. Not a single US airport, port or toll road operator was included, which is not surprising since, unlike Europe, Australia, Asia and increasingly Latin America, the US has few quoted infrastructure operating firms.

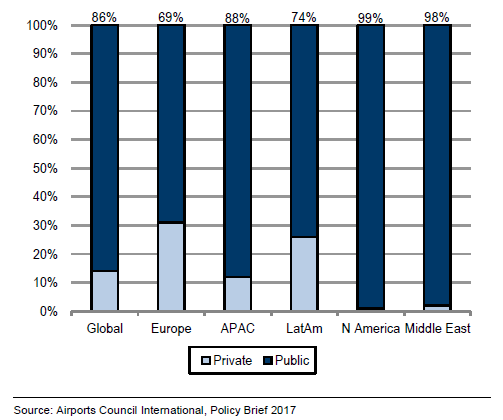

No major privately-owned airports

For example, there are no major privately-owned airports. Most are owned by local and state governments and/or other public entities. The 1996 US Airport Privatisation Pilot Programme resulted in just two airports completing the privatisation process: Stewart International in New York, which reverted to public ownership, and the San Juan, Puerto Rico airport. Currently, there are only three applicants for the programme, the largest of which is Lambert Airport in St. Louis.

The lack of interest could be due to availability of finance, lack of incentives, potential implications for stakeholders and satisfaction with the status quo, and the proposed Legislative Outline may positively impact on the first two factors. Similarly, there are few privately run toll roads in the US, and a high proportion of those are run by non-US concessionaires such as Macquarie Atlas Roads and Cintra (Ferrovial).

Opportunity for experienced, global operators

The proposed legislation may eventually create a supply of newly privatised and listed airports, toll roads, ports and waterworks, but this is not imminent. Investors who desire exposure to US infrastructure operators should instead monitor the activities of established global operators in the target categories outside the US, who also have construction expertise. They are the most likely to be involved in the build-out, renovation and operation of the significant projects in the US.

These firms will include Vinci, the largest infrastructure construction company in the world, and Eiffage, its French alter ego. Other major toll road operators expected to show interest are:

- Macquarie Group (potentially via Macquarie Atlas Roads)

- Ferrovial, which already has extensive North American toll road operations

- Atlantia, which has significant exposure in Latin America

- Abertis, which bid on the Pennsylvania Turnpike

- Transurban, with its interests in toll roads in Washington and Virginia

- Group SIAS of Italy, which has major toll-road holdings in Italy and Brazil, and recently acquired a road construction company in New York.

Security implications

Building new port facilities and operating container terminals may be problematic for international firms due to the US view that port ownership has national security implications. The largest terminal operators in the world, PSA International (Singapore), Hutchison (Hong Kong) and Dubai Ports World may become involved, but Dubai’s forced divestiture in the US in 2006 is a cautionary tale.

Water and waste management companies such as Veolia and Suez, both French, already have extensive US interests and can be expected to participate. Financially-oriented players such as Brookfield Infrastructure, Global Infrastructure Partners, John Laing PLC, 3i Infrastructure and of course Macquarie may show interest as well.

The paradox is that reaping the financial rewards of the US infrastructure build-out by investing in US infrastructure operators is problematic. The investible universe of operators which stand to participate in a major way in the build-out includes many non-US companies with experience in countries where privatisation of infrastructure has a longer history than in the US. Chinese companies have gained much experience building the One Belt, One Way projects, for example, but will they be permitted to participate?

US openness towards heavy foreign involvement is a major concern. The country has become a far more unpredictable place for ‘foreign’ companies, many of which in fact already have a presence in the US. Among other factors, the successful execution of its ambitious infrastructure plan will depend on how open US politicians and government agencies are to outside expertise.