Putin and Powell were certainly the 2 most important figures of 2022 and in a negative sense for the economy and the markets. Of course, we are not confusing the two figures. One is a war criminal and the other a central banker mired in probably the most complex situation in US economic and monetary history.

In any case, we argue that each of them will play a more positive role in 2023.

The war in Ukraine is clearly the most structuring event on the planet, both for 2022 and 2023. And after the Ukrainian counter-offensive was launched, Putin organised arranged referendums in the annexed regions of Donbass, launched a partial mobilisation and launched nuclear blackmail against those who would attack these territories.

This initiative poorly masks the general fiasco of its war launched last February, with a triple liability:

- An economic liability first: internal economic depression (average growth around -3.5% in 2022, nearly 15% inflation); market losses (captive partners of the EU, the North Stream 1 & 2 gas pipeline, loss of many intermediate goods and electronic chips essential to the functioning of its industry, especially military); financial losses (half of the foreign exchange reserves of the Bank of Russia), loss of skilled labour (via emigration), loss of productive capital (via the departure of foreign companies).

- A human liability: the Pentagon has put forward the figure of 80’000 wounded and killed among the Russian military. Other sources put the figure at 30’000 killed (2.5 times more than in Afghanistan). And of course we should not forget the too many victims (civilian and military) in Ukraine.

- Finally, a geostrategic liability (diplomatic isolation, rearmament of Germany and Japan, reengagement of the United States in Europe, end of neutrality of Sweden and Finland, loss of reputation of the Russian army, powerful reinforcement of the military capacities and the spirit of independence of the Ukrainians).

All this has led to the first signs of discontent among the public (new wave of emigration) and the Russian technostructure. It also leads to a growing isolation from its closest allies, China and India, who do not really hide their opposition to the use of nuclear deterrence in the Ukrainian case. Nor do they hide their concerns about the collateral damage of this never-ending war.

Let us be careful, however, because Putin has not yet lost completely and definitively. The arrival of winter and the partial mobilisation may allow him to stabilise the situation. He can also hope that the recession, inflation and energy restrictions will eventually tire public opinion in the West, so that questions about aid to Ukraine will be raised.

Beyond that, we must be aware that a clear victory for Ukraine is not necessarily “desirable”. Not from the point of view of respect for international law or democracy, of course. But from the point of view of geopolitical balances and their consequences on the world economy. Let’s not forget the risk of a Putinian headlong rush and let’s not believe that a successor would necessarily be more conciliatory: Putin is also facing a nationalist opposition that is up to no good. Nor should we neglect the perverse effects of the collapse of Putin’s regime; implosion of Russia (Chechnya, Dagestan…) and/or the former USSR republics in conflict (Armenia-Azerbaijan, Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan).

In the end, it is the Americans who will remain the masters of the game. In any case, the Americans can decide to stop the war whenever they want: all they have to do is stop their aid to Ukraine (about 1.5 billion per month and delivery of arms), with the reservation that Ukrainian nationalism is now very strong and will be difficult to channel. So the US will have to put strong pressure on Zelensky and the Ukrainians to negotiate.

And we think that 2023 will provide an opportunity for that, once military stabilisation returns. We believe that we will return to the conclusions of the Istanbul talks of 29 March (security guarantee for Ukraine, non-integration of Ukraine into NATO, sanctuary of Crimea within Russia) which seems to us the most reasonable and at the same time the most plausible outcome for 2023.

Putin will remain a decisive player in world political and economic life, but in a less negative sense, thanks to his considerable weakening over the past 8 months.

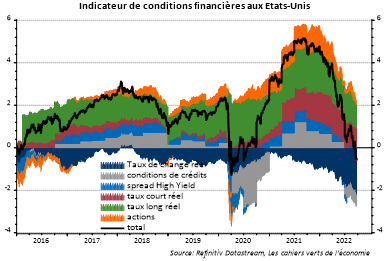

Let’s turn to Powell now. Since mid-August, the Fed’s rhetoric has been getting tougher and Powell’s statements have been particularly hawkish. Rarely in history have we seen such a hardening of Fed rhetoric in such a short period of time. The long real interest rate has risen from 0.4% to over 1.6% in a month and a half (it was negative -1% at the beginning of the year) and it could rise a little more by the end of the year. The market is now pricing in a terminal policy rate of 4.65% for next year, compared to only 3.7% at the beginning of September.

As a result of all this, the financial conditions index has deteriorated considerably further (see chart below). It has now entered recessionary territory.

For a highly indebted and financialised economy such as the US, there is now little doubt that the US will experience another recession in the coming months. This is all the more true given that the US economy is undergoing a very restrictive fiscal policy (unlike Europe), increased geopolitical uncertainties and a self-perpetuating process of falling global demand.

Yet Powell is succeeding in his gamble. Firstly, there are significant improvements in US inflation: a downward trend in energy and manufactured goods prices (thanks in particular to the considerable easing in supply chains and the fall in commodity prices since June).

In addition, the pricing power of companies is beginning to reach its limits (the share of companies considering a price increase has fallen in the NFIB survey).

Last but not least, household and market inflation expectations are falling.

The fact remains that inertia will remain strong. Firstly, there is the problem of rents, which account for 30% of the consumer price index, of which 23% are fictitious rents[1]. Historically, the time lag between the adjustment of property prices (which has only just begun) and rents is around 12 to 24 months.

But there is above all a more general underlying problem: the extreme tension that remains on the labour market (with increases in wages and unit labour costs that have not been seen for a very long time, cf. graph below) despite an already extremely strong macro slowdown.

In part, this reflects a deterioration in the efficiency of labour market matching, i.e. increased difficulty in generating hires based on the level of vacancies and job seekers. The Covid crisis may thus have disrupted the geographical and sectoral movement of employees.

Put another way, the structural unemployment rate (that which favours a sharp deceleration in wage growth that could lead to inflation) has probably increased. Estimated at less than 4% before Covid, some academic authors (L. Summers and O. Blanchard) estimate it at a level close to, or even above, 5%.

This means that in order to stop the inflationary process, the unemployment rate must rise to a higher level than before. And, unless there is a sharp increase in the participation rate, the rise in the unemployment rate will call for a more significant recessionary adjustment in employment.

Since the beginning of the year, employment has been the main variable keeping the US economy (slightly) expanding. And the old Okun’s Law (named after an American economist) reminds us that a 1% increase in the unemployment rate is associated with a 2% decline in US real GDP growth relative to the trend. This process can be understood through a “sacrifice ratio” defined as the cumulative loss in growth associated with a permanent reduction of one point of inflation.

Thus, the price to pay for a halt in US inflation is probably a recession. Powell knows this and acknowledges it. But 2023 will see the foundations laid for healthier growth and Powell will then, unlike 2022, become the linchpin of renewed confidence.

[1] Note, however, that in the PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures Index), the Fed’s favourite price index, the weight of rents is significantly (about 10 points less) lower.