The spotlight in recent weeks has shifted back upon the palm oil industry. The negative connotations associated with the sector have continued to deepen, but there is a growing number of producers who offer a differentiated product, one made with a focus on sustainability. Worldwide, demand for the commodity has continued to rise which brings nations and climate activists to a crossroad, wondering whether sustainable palm oil can be produced whilst fighting climate change.

The good

The versatile nature of the oil has resulted in rapid growth globally, with the fruit-extracted oil becoming an essential product in both the developed and the developing world. Easily transportable due to its semi-solid state at room temperature and its odourless composition, it has become a choice ingredient, now used within 50% of all packaged products. The countless uses range from chocolate to pizzas to biofuels[1].

The largest use of the product is still centred around Asia and Africa, where it is widely used as a cooking oil, essentially acting as a substitute for the more costly alternative of sunflower or olive oil. Despite the origins of the palm being native to a group of west African countries, 85% of global trade is supplied by Malaysia and Indonesia.

Palm oil is a uniquely productive crop when compared with alternative crop sourced vegetable oil. On a per hectare basis, palm oil plantations produce 5-8 times more oil than other crop based derivates such as soya, rapeseed and sunflower.

Additionally, the palms absorb larger amounts of CO2 per hectare per year and emit greater amounts of oxygen into the atmosphere compared to other vegetable crops[2]. Currently, palm oil is grown on 10% of all land devoted to vegetable oils, yet accounts for over 35% of all the vegetable oil production[3].

The Bad

Despite the comparative advantages of the crop, increasing demand has been paired with increased scrutiny concerning the impact it has on deforestation. The environmental cost caused by the commodity has been significant. During the peak deforestation years between 1990 and 2005, 55% of Indonesia’s rainforests were converted into plantations. This in turn has created problems for local ecosystems; changes in the nutrient cycle of the soil which provides for the palms, leading to a deteriorating quality of neighbouring forests and having a negative impact on the plantations themselves[4]. Moreover, illegal deforestation across Indonesia and Malaysia amounted to more than 890,000 hectares in 2018, equivalent to half the size of Wales. The damage caused by global deforestation to the climate is immense. Listed as the second largest contributor to climate change after the burning of fossil fuels, it accounts for nearly 20% of all GHG emissions, a figure greater than the worlds entire transport system.[5] Whereas a new palm oil plantation will sequester carbon at a higher annual rate compared to a regenerating forest, over a period of 20 years oil plantations store between 50-90% less carbon. This denotes the radical difference in the palms ability to combat climate change, not to mention the emissions generated by deforestation in the first place. The consequences of these expansions have in pair led to a decline of biodiversity in the region and resulted in critical endangerment of numerous species including orangutans[6].

A Sustainable approach to palm oil

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) has for the last 15 years aimed to establish a universal system that provides clarity and traceability throughout the supply chain. With a focus on mitigating the economic, environmental and social risks associated to the industry, the RSPO has helped to establish certain parameters for their 4,600 members. These producers have pledged not to partake in any deforestation and to maximise the amount of sustainable palm oil they can produce. The current struggle faced by the members is that sustainable oil only represents 19% of world[7]. Furthermore, the increased costs incurred by producing sustainable palm oil is often not rewarded by a higher price premium on the market, with only an estimated 10% of global demand purchased for being branded as sustainable.

For a considerable period of time, members of RSPO and other local plantations have aimed to minimise their negative environmental impact including emissions and preserve wildlife. Across the region there have been numerous projects to capture methane emitted by production and transforming it into biogas. This in turn has generated electricity for both local operations and the community, limiting the need to burn fossil fuels or finding alternative sources of energy. Furthermore, GHG emissions from certified RSPO mills are considerably lower than that of the industry average. Various schemes across sites have encouraged the reintroduction of wild animals in conservation areas and providing local communities with the means to support animal conservation.

Despite RSPO being a beacon for sustainable production it has not been a journey without criticism. Environmentalists have often condemned the organisation for having too little clarity as to their objectives and for not imposing harsh enough sanctions against members who have partaken in deforestation[8].

Demand outlook

Consumers among OECD countries are demanding greater clarity surrounding the traceability of their products. This has caused a knock-on effect upon large consumer goods companies such as Unilever and PepsiCo who have committed to disclose their entire supply chain.

Nonetheless, the underlying issue lies with increased consumption driven by economic development in third world countries. As has been the case throughout modern history, wage increases and a continuous influx of people migrating from rural areas to cities causes an exponential increase in demand for fatty foods, be it for fast food chains, beauty products or simply for cooking oil.[9] India, Indonesia and China, the largest consumers of the commodity, account for nearly 40% of global demand and as yet they’re imposing few sustainability standards. Compared to the EU, APAC countries demand for the commodity is almost entirely used for cooking and foods products. With over 60% of all vegetable oil imported in India, palm oil accounts for 80% of total vegetable oil used domestically[10].

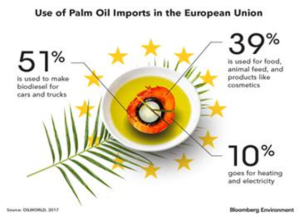

Due to concern about growing deforestation, under a new EU law biofuels will be capped at present levels until 2023 and reduced to zero by 2030. Palm oil imported to manufacture biofuels accounts for half of total EU (excluding UK) imports of the product. The newly approved law has had a partially counterintuitive effect among local farmers, for those who aimed to be sustainable producers are faced with the same prohibition as unsustainable producers. This lack of discrimination among producers could incentivise less environmentally conscientious farmer to further expand their land into biodiverse rainforest and shift their supply onto the Asian arcade.

In order to circumvent this ban and the potential damage to the local economy, the Asian region is placing greater importance on producing a sustainable product and pledging to protect their rainforests. A new initiative by the Malaysian government will force both large and small plantations to adhere by the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MPSO) Certification Scheme. This program is particularly aimed at encouraging smallholder farmers, accounting for 40% of harvest, to follow international standards and combat deforestation.

Britain’s foreign secretary Dominic Raab took a somewhat alternative approach in comparison to his European counterparts on a recent post-Brexit trade mission.[11] Given the importance of the product to their respective economies and the environmental debate against it, Mr Raab shifted the support of Britain behind that of the Malaysian sustainable palm oil producers. This provides encouragement to local farmers and plantation owners to produce a traceable and clean commodity. The eventual aim of this partnership is to combat climate change, through reforestation and a stricter environmental code, all whilst maintaining an industry which provides directly for 4.5 million people.

Alternatives?

It should be noted that there has been considerable investment directed at finding alternatives to food oils but with very limited success yet. In order to affirm the 2°C target established through the Paris Agreement, there must be greater cohesion among member states to set a common direction and unilateral regulation. The complete boycotting of the most efficient oil crop could be potentially devastating compared to the regulated production of sustainable palm oil.

[1] https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/8-things-know-about-palm-oil

[2] http://www.ukm.my/ipi/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/29.2009The-Environmental-Impact-of-Palm-Oil-and-Other-Vegetable-Oils.pdf

[3] https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/8-things-know-about-palm-oil

[4] https://www.spott.org/palm-oil-resource-archive/impacts/environmental/

[5] http://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/en/

[6] https://www.spott.org/palm-oil-resource-archive/impacts/environmental/

[7] https://rspo.org/about#vision-mission

[8] https://news.mongabay.com/2018/07/rspo-fails-to-deliver-on-environmental-and-social-sustainability-study-finds/

[9] https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/feb/19/palm-oil-ingredient-biscuits-shampoo-environmental

[10] http://mpoc.org.my/indias-sept-palm-oil-imports-up-21-on-festive-demand/

[11] https://www.ft.com/content/73cfcc56-5a24-4576-87af-c529f9a34d36

Important Information

The information contained herein is provided for discussion purposes only, is not complete and is not, and may not be relied on in any manner as, legal, tax or investment advice or as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase an interest in securities. QUAERO CAPITAL believes the information contained herein to be reliable and has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but no representation or warranty is made, expressed or implied, with respect to the fairness, correctness, accuracy, reasonableness or completeness of the information and opinions.

The estimates, investment strategies, and views expressed herein are based upon current market conditions and/or data and information provided by third parties and are subject to change without notice. There is no obligation to update, modify or amend these materials or to otherwise notify a reader in the event that any matter stated herein, or any opinion, projection, forecast or estimate set forth herein, changes or subsequently becomes inaccurate.

These materials include certain opinions, statements and projections provided by Quaero capital with respect to the anticipated future performance of certain asset classes. Such opinions, statements and projections reflect significant assumptions and subjective judgments by QUAERO CAPITAL’s management concerning anticipated future events. these forward-looking statements are inherently subject to significant business, economic and competitive uncertainties and contingencies, many of which are beyond QUAERO CAPITAL’s control. In addition, these forward-looking statements are subject to assumptions with respect to future business strategies and decisions that are subject to change. The data as presented has not been reviewed or approved by any party other than QUAERO CAPITAL.

Nothing contained herein shall constitute any representation or warranty as to future performance of any financial instrument, currency rate or other market or economic measure. Opinions expressed herein may not be shared by all employees of QUAERO CAPITAL and are subject to change without notice.