The emergence of generative AI has technological, macroeconomic, societal (social, spatial and generational inequalities), managerial, demographic (life expectancy), political and geopolitical dimensions.

Of course, we don’t have the time in this column to go into precise and extensive detail on generative AI, and we will obviously return to the subject in greater detail in subsequent publications.

First of all, it should be remembered that generative AI is only the latest avatar of AI (defined as the ability of machines to imitate human intelligence), the development of which began in the 1950s (Turing machine). The first conversational robot (ELIZA) was born in the 1960s. But it was not until the 2010s that we saw a clear acceleration in both fundamental and applied research.

This has manifested itself in an explosion of research and publications/books, but also in a massive increase in investment flows in this area (see graphs below).

Share of books listed by Google containing expressions on artificial intelligence, deep learning and machine learning

Sources: Google, Cahiers verts de l’économie

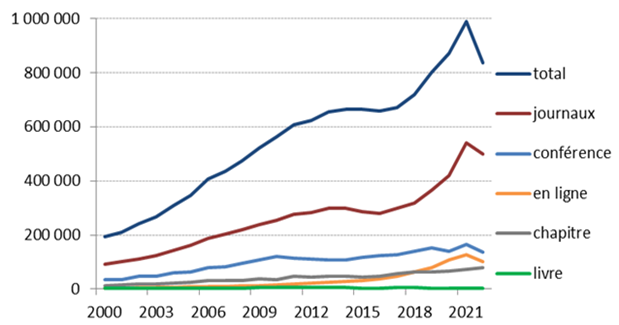

AI: number of total annual publications worldwide

(total, journals, conference, online, chapter, book)

Sources: QCDE, Cahiers verts de l’économie

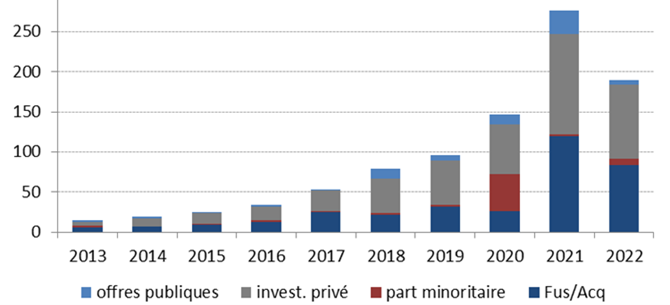

AI: business investment by source of finance

(in USD bn) (public offerings, private investment, minority share, merger/acquisition)

Sources: Netbase Quid (2022), Cahiers verts de l’économie

In terms of patents, the increase is just as impressive: 140,000 in 2021 compared with 2,500 in 2010.

The release of ChatGPT by Open AI in November 2022 (ahead of the launch of Bard in Europe by Google), followed in the spring by the sharp upward revision of Nvidia’s guidance on its 2023 earnings expectations due to AI, have fuelled strong investor interest in generative AI.

Generative AI is a technology with the ability to create new content in the form of text, images, video, audio and code, with the user formulating his or her request in natural language rather than using a programming language. Until now, to carry out specific tasks, AI has involved programmers writing code and needing to collect a mass of learning data to train a neural network.

Like the role of the calculator in mathematics, generative artificial intelligence can replace humans in certain unitary tasks of reading, writing or conversation. It can also, and above all, increase human capacities, thanks to the ingestion and cross-referencing of gigantic volumes of information, synthesis functions and the generation of raw textual material. There are still real limits to be overcome, notably the loss of traceability of sources, data confidentiality, time delay, the illusion of precision in the content generated, which may turn out to be inaccurate, errors of interpretation and cognitive biases that take a long time to correct.

What is the macro impact?

As with all innovations, the main questions relating to generative AI concern its scale (its potential for disruption) and its speed of dissemination.

Generative AI is a general-purpose technology and can affect virtually all sectors and areas of activity to varying degrees. AI therefore has the potential to be a major disruptive transformation for the economy as a whole. And at quite a fast pace.

Historically, even major technological innovations have been slow to percolate. Their effects on productivity were not immediately visible. The explosion in productivity due to the electric motor and the personal computer occurred around 20 years after the technological breakthrough, at a time when around half of businesses had adopted the technology.

But generative AI is an innovation that already benefits from a general infrastructure and abundant intermediate goods: the computing power of computers is constantly increasing, while the infrastructure of the internet network is already there. Nor, for the moment, does it seem to be encountering any significant sociological or psychological resistance.

Two months after its launch, ChatGPT has already surpassed 100 million users. What’s more, and this ties in with the 1st comment, the question of price does not currently seem to be a major obstacle for businesses.

Nevertheless, it will take several years for significant deployment to take place. For the time being, the rate of adoption of AI by American companies still seems marginal.

As far as the labour market is concerned, there is no doubt that generative AI will accelerate the automation of a number of tasks, which will save time, increase productivity and reduce labour costs for businesses.

Estimates vary, but we can assume that in developed countries more than half of all occupations will be exposed to at least some degree of automation by AI over the next 10 years, and that most of those exposed will have a significant proportion of their workload (around 20-30%) that can potentially be replaced.

Exposure is particularly high in the administrative and legal professions (around 40-50%) and, more generally, in sectors where many employees spend a lot of time performing tasks that AI models are well suited to automating (translation, data research and analysis, writing summaries and summary reports, voice and video generation, etc.).

Conversely, they are weak in physically intensive professions such as construction, catering, personal services or maintenance.

Automation linked to generative AI could increase global productivity via 2 channels:

- Workers would use generative AI to save time (automation of repetitive tasks with no added value, documentary and statistical research, etc.) and devote more time to other productive activities.

The transformative potential of generative AI has already begun to translate into reality. According to some studies[1], AI has a significant influence on the speed of execution of medium-level professional writing tasks.

Other studies[2] highlight the impact of a conversational assistant based on generative AI for customer support (productivity increased by 14% on average, mainly among novice and low-skilled workers).

Other more general studies[3] tend to show that the adoption of AI leads to an annual increase of 2 to 3 points in labour productivity growth for several years.

- the jobs destroyed would then be partially replaced by new jobs of varying degrees, difficult to quantify today, but with higher levels of productivity.

These new jobs would be :

- Either linked to generative AI and as yet unknown. The Internet has given rise to the profession of web designer. It should not be forgotten that today, around 60% of workers are employed in occupations that did not exist before the war. Over 85% of the growth in employment since the 2nd World War can be explained by the creation of new jobs through technology.

- In other words, due to the surplus growth generated by the increased productivity of non-displaced workers.

However, the overall scale of productivity gains due to the widespread adoption of AI is highly uncertain. It will ultimately depend on a number of factors: the level of difficulty of the tasks that generative AI can perform; the number of jobs automated (increase in the productivity of workers who will remain in post and use AI; increase in productivity linked to the replacement of workers by AI); the speed of adoption; the potential of human capital given the already high level of education; inequalities in access to digital technology (cost/education/training), etc.

What about the impact of generative AI on equity markets?

How can we justify investors’ recent enthusiasm for generative AI?

For 2 main reasons:

- Firstly, generative AI is a broad theme with major disruptive potential. It is a major innovation, like the PC in the 80s, the Internet in the 90s, mobile phones and smartphones in the 2000s, and the cloud in the 2010s. This is in contrast to some of the ‘flashy’ themes of recent years (3D printers, autonomous driving, the metaverse, etc.).

- Secondly, there has been a rapid translation into concrete results in companies’ earnings announcements (Nvidia’s guidance was raised, after which investors significantly raised their earnings expectations). This is in contrast to the “blockchain” theme, for example, which also has long-term disruptive potential, but which is struggling to find concrete expression in company results.

In our view, we need to distinguish between the impact of generative AI on the companies that are the main immediate and direct beneficiaries of AI, and the impact of its longer-term dissemination to the market as a whole.

Concerning the first companies, we distinguish 3 sub-groups:

- Companies that market AI (e.g. Google);

- Companies that produce the equipment and semiconductors needed for AI (e.g. Nvidia);

- Companies that use AI to develop their business significantly and have the corporate culture to do so quickly (e.g. Facebook).

Furthermore, the value of generative AI stocks in terms of diversification does not seem clear at this stage. The correlation of AI trackers with the Nasdaq has been very high since 2019 and the beta is fairly close to 1. The alpha generated by this theme does not therefore seem obvious on a historical basis, although this could change.

This can be explained by the consanguinity of AI trackers with the Nasdaq (AI trackers incorporate all the big names in Big Tech with high weightings). What’s more, many companies in the AI ecosystem are start-ups that are not listed (e.g. DeepMind, OpenAI, etc.).

Turning now to the market as a whole, the medium-term impact of generative AI seems fairly positive to us, given the additional GDP growth that its implementation will generate. It is also likely to boost the margins of AI-using companies.

However, these forecasts need to be tempered by the risk of increased taxation (as the adoption of AI contributes to further distorting the distribution of added value towards profits at the expense of labour) and by the risk of a rise in the real neutral rate on the bond markets, which would be unfavourable for valuations.

Moreover, valuations on US equity markets are already high (and the risk premium has fallen sharply in recent months).

All in all, it does not seem unreasonable to expect around 0.5-1 point of additional annual upside for developed equity markets once AI is widely adopted (in 5 to 10 years’ time).

However, we need to be wary of long-term euphoria, remembering that major phases of productivity growth have historically been accompanied by equity bubbles (1920s, 1990s) that eventually burst/deflate.

Our experience of themes shows that we are often dealing with N-shaped curves in terms of performance:

- An initial phase of strong enthusiasm for the theme (everyone buys at any price): the rise in prices is driven solely by the expansion of multiples.

- This is followed by a phase of disappointment (innovation fails or takes longer than expected: i.e. investors have overpaid for earnings growth), leading to a phase of normalisation of valuations.

- Finally, there is a third phase of recovery, supported by earnings growth, when the innovation has matured and is beginning to bear fruit.

Obviously, each phase can last from a few months to a few years.

The obvious recent parallel from this point of view is the internet bubble of the late 90s, its bursting in the early 2000s and then a resurgence of the sector driven by rising earnings.

[1] Noy et Zhang, 2023

[2] Brynjolfsson et al, 2023

[3] Alederucci et al., 2022 ; Czamitzki, Fernandez et Rammer, 2022 ; Behrens et Trunschke, 2020 ; Acemoglu et al., 2022 ; Bessen et Righi, 2019