Whether we like it or not, geopolitics has and will continue to play a decisive role in the economy and financial markets.

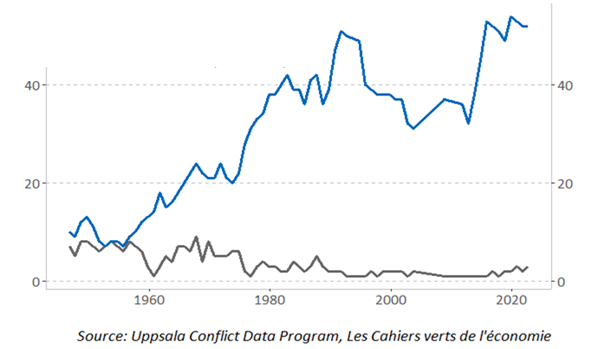

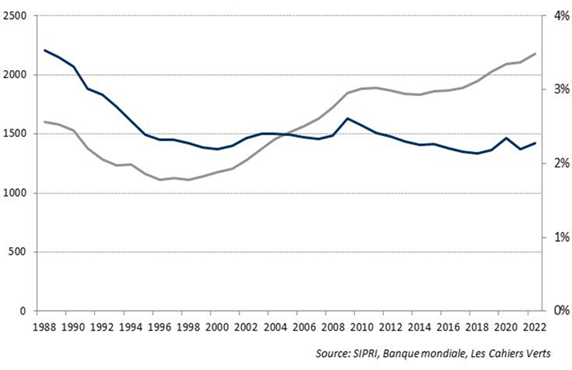

After the illusions of the post-Berlin Wall era (1989) and the end of the USSR (1991) (‘peace dividend’) in the 1990s, the world went through a period of growing international tensions, symbolised at the start of the century by Vladimir Putin’s rise to power in Russia in 2000 and the attacks of 11 September 2001. Symbols of this development are the rise in military spending around the world and the increase in the number of conflicts (see graphs below).

Number of armed conflicts and wars 1946-2022

(blue line: external armed conflicts with >25 dead; grey line: internal armed conflicts with >25 dead)

World – military spending in 2021

(grey line: in billions of constant dollars – left scale; blue line: as a % of world GDP – right scale)

Today, the vectors of these tensions are multiple (imperial ambitions and religious fanaticism, climate shocks and the quest for climate justice, the struggle for technological leadership, migratory transfers, etc.).

The West is not without responsibility. Military initiatives in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria have weakened its credibility over the last twenty years. The West has also shown itself to be naïve, in particular through the illusion that the development of trade with China would encourage its democratisation, notably when it joined the WTO in 2001, even though China has never experienced democracy in the Western sense. The failure of Russia’s democratic transition in the 1990s also led to Putin’s accession. Germany’s attitude under Angela Merkel for more than 15 years has also considerably weakened Europe’s strategic position: disarmament, energy vulnerability, migratory flooding, narrow mercantilism, etc.

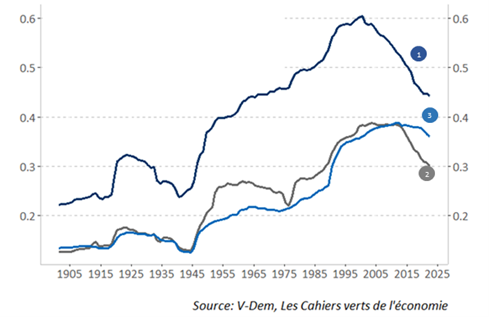

At a global level, this weakening of the West and this rise in tensions have been accompanied by a decline in democracies. The proportion of complete democracies in the world is falling. And the weight of democracies, as a percentage of GDP or population, is in the minority (see graphs below).

World – democracy index (0-1 scale)

(1-GDP-weighted average; 2-population-weighted average; 3-simple average)

World – breakdown of countries by democratic regime

(1-authoritarian regime; 2-hybrid authoritarian regime; 3- partial democracy; 4-full democracy)

Western democracies have themselves experienced a weakening of their governance linked to the impotence and slowness of their adjustments for various reasons (lobbies, corporatism, the growing burden of debt, pressure from active minorities and social networks, frustration among the middle classes, etc.).

It should be noted that authoritarian systems have not only become stronger, they also have imperial ambitions (Russia, Turkey, Iran, China, etc.), which means that the democracies they despise are also fragile from the outside.

From this point of view, democracy is weaker from the outside in Europe than in the USA. The United States has been able to maintain – and even increase – its economic, technological and military power in recent years. But it is more threatened from within by the cold, virtual civil war that is sweeping the country. With Joe Biden’s inability to reduce the extreme political polarisation and his inability to step down and prepare his succession.

The risk is not that of a dictatorship in the USA (strength of the judiciary, the press, the federal states, etc.), but rather of America turning in on itself, with Europe the main victim. A Trump victory in 2024 would represent a further isolationist move against Europe, multilateral institutions, NATO and Ukraine.

On the other hand, Europe, while appearing a little more solid internally, is under multiple external attacks: jihadist terrorism, Islamist propaganda, disinformation, food and energy pressure (Russia), migrant flows (Turkey) and cyber attacks (Russia).

Europe is not to blame for everything. It has been less naïve over the last 3 years. It demonstrated its ability to create solidarity (by issuing joint debt and North-South transfers) during the pandemic. It has committed €2 trillion between now and 2027 (if we include the multiannual budget of €1.2trl between 2021 and 2027), including €807bn for the Next Generation EU plan, i.e. around 8% of GDP. It has also largely succeeded in overcoming the gas and energy crisis of 2022. There are also some signs of a return to an industrial strategy and reindustrialisation.

Be that as it may, the war in Ukraine and the current conflict in Gaza show that the main risk is that of compartmentalisation or fragmentation of the world.

The fragmentation of the global economy is a greater risk than simple deglobalisation (a decline in the weight of trade in goods, services, people, capital, etc.).

It means growing heterogeneity between regional blocs and/or countries and/or alliances, driven by necessity (health risks, technological and cyber risks, protectionism, legal risks, etc.) or geopolitics (increasing number of sanctions, embargoes, etc.).

It would be a world with divergent commercial, legal and technological standards, different payment systems and reserve currencies, with the international status of the dollar being called into question following the sanctions on Russian foreign exchange reserves and the excesses linked to the extraterritorial status of the US currency.

Inevitably, this would result in higher inflation and nominal long-term interest rates, a decline in international cooperation (particularly on climate change) and weaker economic growth, particularly in emerging countries (which have benefited most from the integration of value chains over the last 40 years).

The rise in nominal long-term rates is due to three factors:

- Rising inflation expectations and inflation

- Less transfer of flows from saving countries (commodity exporters, China, etc.) to the USA

- Challenges to the dollar’s international status

We are not there yet, but this is the greatest risk.

Global macro-politics will continue to dominate in 2024, with elections not only in the United States but also in Taiwan, India and other major countries (Indonesia, Pakistan, Egypt, South Korea and Mexico), not to mention the European elections.

How should we approach these challenges in terms of investment strategy?

Of course, gold comes to mind. This is all the more true given that the price of gold appears to be moderate relative to all commodities, after having reached a very high level in 2020. The ratio of gold stocks to GDP does not appear to be too high. And the potential for a further rise in real interest rates seems very limited.

We are also thinking about defence stocks. The euphoria over the defence sector that followed the outbreak of war in Ukraine in February 2022 has subsided in 2023: valuations have deflated and expected EPS have declined. The latter are stabilising and the market appears less expensive (12m PE of 14.8x, i.e. a 2% discount to its 10-year average, in line with that of the MSCI World).

But we can also bet on stocks that will benefit from industrial relocations.

A final word on infrastructure, which has its place in this strategy. In addition to its attractiveness in terms of asset management (diversifying portfolios, regular contractual cash flows, resilience throughout the economic cycle, protection against inflation, etc.), infrastructure will play a full part in Europe’s energy and technological autonomy.