Infrastructure is an attractive asset class overall for a number of reasons: diversification in portfolios, contractual and regular cash flows, resilience over the economic cycle (low beta), vital importance to society (digital and energy transition) and the benefits of longevity.

Protection against inflation

Investors also often see the infrastructure asset class as a good way of hedging against inflation. One of the main characteristics of this sector is that the companies in question often benefit from price indexation formulas built into their contracts. But the definition of infrastructure continues to evolve and its scope to expand. It is therefore essential to take a nuanced view of each asset to check whether it really has the usual characteristics of the infrastructure sector.

The potential ‘inflationary benefits’ of infrastructure assets depend in fact on the strength and flexibility of their revenue streams, cost structures and balance sheets.

What about rising interest rates?

From a general point of view, the impact of rising interest rates should be negative, as this affects discount rates and refinancing costs.

In the event of an economic slowdown, or even recession, infrastructure operators need to have manageable levels of debt so that the costs of servicing their debt are more than covered by cash flow and to limit any refinancing risk.

Experience shows, based on listed assets, that infrastructure assets are sensitive to levels of and changes in real interest rates. However, this sensitivity varies over time. For example, it was higher in the MSCI Infrastructure than in the MSCI World from 2012 to 2017 (longer duration) and lower from 2019 onwards (shorter duration).

The period from 2012 to 2017 was marked by a higher valuation of infrastructure thanks to negative real interest rates.

And it is undeniable that the real rate shock of 2022-23 has affected the performance of infrastructure assets. Initially, rising inflation benefited the sector. But thereafter, there was a sharp underperformance of infrastructure linked to a fairly powerful derating (see chart below).

will interest rates remain high?

The real question today is whether real interest rates will remain high (2% in the USA), or go even higher. It should also be noted that it is the real rate (and not the nominal rate) that is important for infrastructure and for the economy in general in the medium term. Investors make investments with given prospective (real) returns (independent of inflation). Any increase in expected inflation has an impact on both the financing rate and the selling prices of the goods or services offered over the time horizon in question.

A 1st source of explanation for a higher real neutral rate could be the recent rise in US real potential growth. The resilience of US macro growth (2% in H1 and around 3/4% in Q3) despite the Fed’s monetary tightening would bear this out. The good productivity figures for Q2 and for the working-age population (linked to the return of immigration since Biden), as well as the rise in the participation rate (to 62.8%, the highest since the pandemic, and the highest for 15 years, for the 25-54 age group) also bear witness to this.

A 2nd source of explanation would be more negative. The rise in the US real interest rate could be due to a savings/investment imbalance. This would be the consequence of growing and substantial investment needs (energy/digital transition, financing defence spending, the war in Ukraine, etc.) in the face of lower available savings from the world’s big savers (the Gulf, Germany, Russia, China, etc.).

It should be noted in particular that a number of net oil-exporting countries are aware of the need to diversify their economies in the medium and long term as a result of the energy transition, hence their efforts to invest domestically to the detriment of their ability to invest externally (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Nigeria, ….). This shock is reminiscent of the shortage of global savings mentioned in the early 1990s following the shocks associated with German reunification and the transition in Eastern Europe.

Added to this is a growing mistrust of Treasuries and the dollar for political reasons, particularly since the US administration imposed sanctions on Russia. This is reflected in the downward trend in non-resident investors’ holdings of US sovereign bonds.

We are not certain of the precise mechanical impact of these phenomena on the level of equilibrium real long-term rates. But we do think that they are at least influencing bond investors’ expectations and that they are positioning themselves on higher neutral rates.

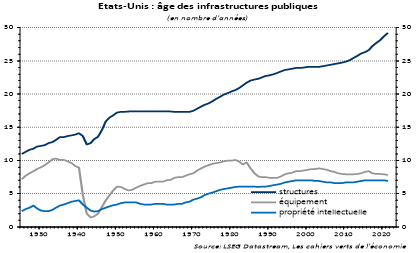

What are the consequences for infra? This will undoubtedly result in a greater dispersion of performance between infrastructure assets, which will offer opportunities to well-established, solidly capitalised companies, particularly if they manage to acquire and integrate smaller assets. The political impetus in both the US and Europe remains favourable, and infrastructure needs remain substantial. The average age of traditional infrastructure continues to rise (see below).