Market commentators have spent a lot of time in recent months on the relative merits of “value” and “growth” styles of investing. As readers will know, we are firmly in the “value” camp, but it is important to define what this actually means.

To us “value” investing does not just mean buying the cheapest stocks: what it means above all is finding the companies where the fundamental valuation criteria fit the business and the outlook. Valuation is the beginning and end of investment for us, and that is why we stood in amazement at the valuation ratios of NASDAQ and technology stocks looking back 18 months. Now it is clear that the froth has been blown away and valuation matters again.

What we have seen is the “gravitational pull of fundamentals” as the exorbitantly over-valued shares and concept stocks which had driven markets higher over recent years have started to come back down to earth. Concept stocks that do not have a medium-term path to value creation through net profits are being dumped and have led markets lower. This means that “value” shares (or simply companies creating value and trading at sensible multiples) have so far fallen less than indices. The rise in interest rates has also accelerated this trend towards shorter duration assets which produce profits now rather than further away in the future.

Rather than a classic “growth” to “value” rotation that investors can play tactically for the short term, we have observed the beginnings of a more structural shift from “growth at any price” to “valuation counts” or what we could call “fundamentals investing”. The market may be shifting from « I liked the product so I bought the shares » irrespective of valuation, to « this is a good business with competitive advantages and barriers to entry, positive returns on invested capital, dividends, a solid balance sheet requiring no refinancing and an attractive valuation ». On one hand, the IPO of the hyped “greentech” stock in Germany, Compleo, illustrates the first attitude: a player in the exciting area of electric charging stations, which shares have fallen circa 90% over the last two years. On the other hand, U-blox, a Swiss GPS module and chipset designer, is an example of the second attitude. It rose by almost 90% over the same period. This Swiss small cap name has started to reap the benefits of its CHF 1bn investment (equivalent to its market cap) in R&D over the past 20 years, building a strong competitive advantage, high barriers to entry, all this while being debt free.

In the “value” versus “growth” debate, we might question whether “growth” can really be opposed to “value”. It might seem more logical to consider that “expensive” (or even “overpriced”) be the opposite of “value”. The confusion may have come from quality growth companies recognised as such generally being highly rated by the market. But this does not take away our quest to find quality companies with solid balance sheets and strong business models that are trading at a low price/valuation because they are misunderstood or overlooked, or because they have been over-sold following a temporary negative issue. Being contrarian is an important part of being a “value” investor.

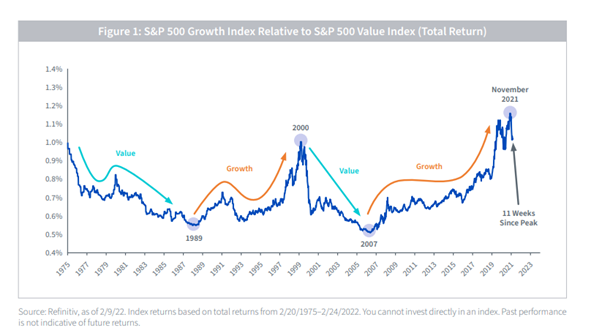

We are convinced that the sea-change in the market is here to stay for a good while. Style changes of this magnitude do not come and go in a matter of months. The chart below (going back to 1975) clearly shows that when there has been a trend reversal, it has tended to last for years. The gung-ho era of the internet bubble of the late Nineties was followed by the DotCom bust and the next five years saw a real boom in interest in “value”. So much so that we do remember a time in 2005 which saw a dearth of reasonably priced “value” stocks. Eventually it was “value” that became over-priced… but we may see several good years for “value” investors before we get to that point.

There are currently plenty of risks inherent to investing. The global outlook is complicated to say the least. However, we can be sure of one thing which is that buying “good” companies at “great” prices is a long-term strategy that delivers outperformance.