Reminder of portfolio management strategies

We have already written a great deal about central banks, and we will return to the subject again in this monthly report. On the subject of monetary policy, the borderline between forward-looking analysis and repetitive rhetoric has now been reached. The Swiss National Bank’s (SNB) surprise start to the cycle of key rate cuts does not revisit the subject (the SNB’s decision is also motivated by a problem of overvaluation of the Swiss franc), or even the fashionable thesis that the ECB could finally cut rates before the FED. The duration of a longer-than-expected pause, which has been our scenario since last year, has now been taken on board by the markets. Additional volatility would come from an acceleration in the timing and pace of the downturn. With this in mind, we are comfortable with our ‚cruising‘ duration of 4.

In our latest Flash publication, we set out our views on the credit market, particularly High Yield. We believe that the part of our investment universe most exposed to financial leverage (B-grade ratings) has been weakened by the length of the pause observed by central banks. We therefore believe that, against a backdrop of increasing idiosyncratic risk, a strategy aimed at enhancing the credit quality of the portfolio by accepting a less favourable recovery on default in exchange for a better credit profile (equivalent senior IG rating or even subordinated rating for our Tier 2 banks) is appropriate. This strategy involves strengthening the hybrid corporate and financial subordinated pockets (we always exclude AT1/CoCo/RT1) by arbitraging against the single B segment and even certain BB securities whose relative price we do not feel is justified.

Is geopolitical risk a market risk?

The resurgence of idiosyncratic risk after two years of undivided domination by macroeconomic considerations prompts us to reconsider the weight of more ‚lateral‘ risks such as geopolitical risk. Although geopolitical risk has featured prominently in market discourse and analysis since Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and the simultaneous escalation of historical conflicts (Israel-Iran/China-Taiwan), paradoxically it has weighed very little on the financial markets.

For the record, the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army immediately sent the German 10-year yield plunging by 30bps, but it returned to its initial level two weeks later, just a few days before the FED launched the most powerful round of global monetary tightening for forty years. If there can be no doubt about the considerable geopolitical importance, even existential for Europe, of the return of war to its soil on 24 February 2022, there can be little more doubt about the marginal nature of its impact on the financial markets compared with the deflagration produced on the latter by the FED’s decision to raise its key rates on 15 March 2022. It could be argued that the Russian invasion and the sequence of sanctions and counter-measures caused a similar explosion on the markets by triggering the inflationary crisis via the energy crisis. This would be to overlook the fact that the former began well before the latter, particularly in the United States where inflation imported through energy prices played a far less important role than in Europe.

If we had to sum up the influence of the war in Ukraine on the markets, the first sentence of Hemingway’s short story „In Another Country“ would be an excellent choice: „In the fall the war was always there, but we did not go to it any more“.

This lack of evidence of the existence of a causal relationship, or at the very least of a durably identifiable influence, is due first and foremost to the definition of geopolitical risk, which encompasses a wide variety of situations, from armed conflict to climate catastrophe to Brexit. We will confine ourselves to the classic but very robust framework of political, economic and military relations between sovereign states, assuming that geopolitical risk arises when the normal course of relations between states or between regional blocs is threatened. The issues covered by the geopolitics of commodities, a highly developed area of analysis, are therefore largely taken into account, even if episodes of commodity crises and geopolitical crises in the sense of military tensions do not always overlap.

The difficulty of isolating geopolitical risk from all the risks that may be involved in a market event is also due to the complexity of measuring it. Stock market volatility indices (VIX, V2X for the S&P 500 and the Euro Stoxx 50) and bond market volatility indices (MOVE for US Treasuries), which can easily be seen to include geopolitical risk, are used by default.

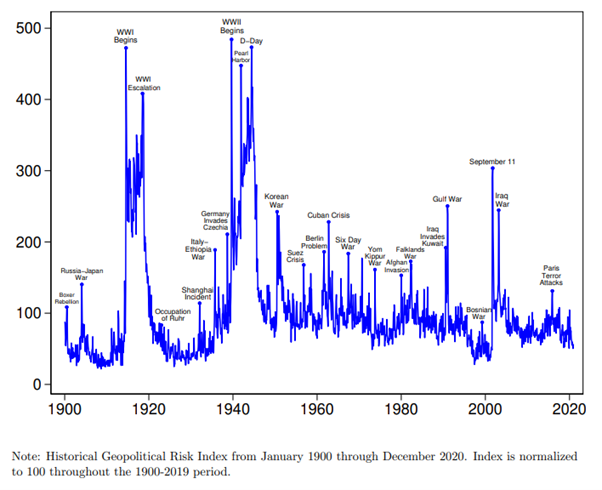

There are, however, specific indices developed mainly by central banks, including the Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR) created by two FED economists and detailed in a 2021 research paper. The index is based on a textual analysis model fed by the digitised archives of eleven American, British and Canadian newspapers. The model counts the number of times certain key words appear, such as ‚military tensions‘, ‚wars‘, ‚terrorist attacks‘ (excluding associations such as ‚economic war‘ or ‚trade tensions‘) and deduces a level of risk. The graphs below show the evolution of the GPR index from 1900 to 2020. Among other observations, the authors note that :

- Generally speaking, for the United States, periods of significant increases in the index (>200) are associated with periods of slowdown in global economic activity and poor performance on the equity markets, without it being possible to deduce a causal relationship. Industrial production, employment and trade also seem to be having a lasting impact.

- The financial (equity) markets seem to be more affected by a geopolitical threat that is prolonged than by the transformation of this threat into an actual crisis. This is the idea behind the stock market adage „buy the rumour, sell the news“. This phenomenon is not unique to the US context: in defeated France occupied by Germany, French share prices quadrupled between 1940 and 1943 and property prices increased fivefold, while rents were frozen and buildings subjected to Allied bombing.

The ECB has also developed a similar indicator dedicated exclusively to the Ukrainian conflict. The War News Index searches a large number of newspaper articles for the words Russia AND War and Ukraine AND War, using the Dow Jones Factiva platform’s comprehensive database.

While the ECB’s indicator is of little practical use, the scope and historical depth of the GPR index make it possible to observe the behaviour of a number of assets/indices that are representative of risky and defensive investments made during periods of geopolitical crisis that are well defined in time: the Gulf War, the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001, the war in Iraq. The table below shows the cumulative performance of the S&P 500, the MSCI World, gold and the 10-year Treasury for each of the selected examples:

| S&P 500 | MSCI World | Gold | 10Y UST | |

|

Gulf War August 90 – February 91 |

-14,2% | -9,6% | +6,4% | +1,9% |

|

11 September Sept – october 2001 |

-14,9% | -14,7% | + 8,9% | +4,1% |

|

Iraq war January-March 2003 |

-10,2% | -9,9% | +9,6% | +5,6% |

Source: Quaero Capital, March 2024

In line with the results presented in the FED’s research paper, equity markets began to recover very soon after the crises broke out. Over a six-month period following the end of the crisis, they outperformed defensive assets, albeit with greater volatility. Of course, the sample is too small to conclude that geopolitical risk should not be taken into account in an investment strategy.

All we can say is that, despite the large amount of exogenous information constantly influencing the markets, there seems to be a high degree of stability in the hierarchy of risks perceived by the markets. The current context, in which monetary and fiscal issues are at the top of this hierarchy, despite a backdrop of acute geopolitical tensions, is exemplary in this respect. The forthcoming normalisation of monetary policy could, however, change this picture.

Source : FED, November 2021